Is More Transparency Always Better?

A historical perspective, coupled with a recent event in my city, has suggested "always" is a strong word.

We’ve heard it said over and over again by activists on both sides of the aisle. For over a decade, liberal activists have demanded more transparency from local police departments. On the conservative side, you’ve heard calls for federal government transparency.

Police departments across the country have brought in civilian oversight boards to facilitate this request on behalf of liberal voters. Organizations like the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) have been erected to satisfy the demands of conservative voters.

I’m sympathetic to the assertion that more transparency is always better when it comes to the government. It runs on our tax dollars. We deserve to know what the government is doing with it. More than that, they’re supposed to serve the people, so the people have a right to know what they’re doing, even if money was no object.

On the other hand…

How’s That Been Working Out?

We’ve been in an era of greater transparency and accountability in policing for the last decade. At least since Michael Brown was killed in Ferguson, Missouri and really going even further back to Rodney King and the LA Riots.

In all that time, has this greater transparency and accountability made things better? As I said, I’m sympathetic to the argument that more transparency is always better, but not only does that violate the rule against speaking in absolutes, the results haven’t been all that great.

Community policing, police legitimacy, procedural justice, and all the other concepts and principles that police departments have adopted since the 1990s have seemingly borne little fruit for improving public sentiment toward the police.

In fact, policing has been at or near its lowest levels of trustworthiness with the public since all these transparency measures were widely implemented. It has only recently seen an uptick as the BLM organization has been exposed for the grifting scheme it always was.

I think I have some idea of why all this transparency hasn’t been having the desired effect.

We’re Listening to the Wrong People

Transparency isn’t good or bad. It’s a neutral concept. The police are doing nothing more than reporting what they’re doing to the public. It’s intended to be entirely fact based. The trouble is, we live in the age of social media.

As the saying goes, a lie can travel halfway around the world while the truth is putting on its shoes. A police encounter can be edited out of context and sent across the globe before a police chief is even aware the incident happened; much less been briefed on the facts.

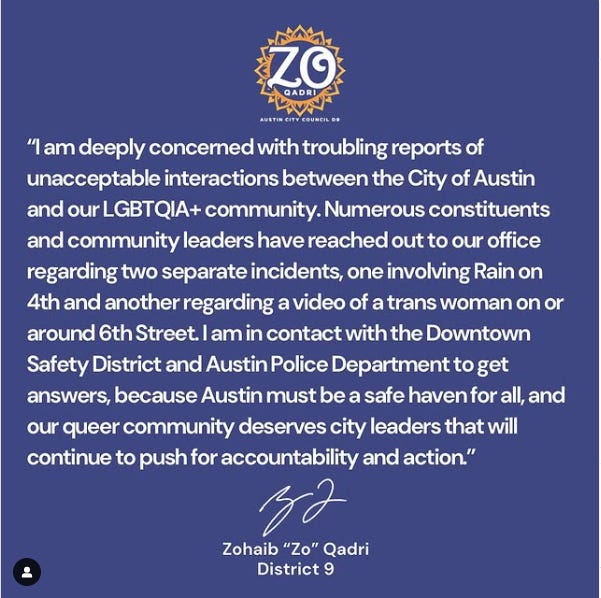

This happened recently in my town. A city councilmember caught wind of a viral incident wherein officers arrested an individual in what appeared to be a rough manner and immediately called for increased transparency and accountability from the police department. The facts of the case weren’t even fully understood at the time.

By the time it was discovered the individual had assaulted someone in front of officers and was resisting arrest, causing officers to use force to detain them in handcuffs, the narrative was already set. Oh, and the individual tripped on their own shoes. In the clipped-out-of-context version of events, it looked like the officers acted with undue aggression. The body camera video, as usual, shows a bit more context:

Ignoring the fact that, legally speaking, the officers would have been justified in performing a take-down against a resisting individual, they didn’t even do that. The person tripped over their own shoes as they attempted to get away from the cops while the cops were pulling their hands behind their back.

None of that matters though. The facts don’t matter when an incident goes viral. The first take is the most important one. Police departments are reactive when it comes to these incidents. They catch wind of a public reaction to what officers are doing and then respond. To my department’s credit, the chief responded appropriately with a press release. Nevertheless, it was still a reaction, which is the nature of the beast.

So, if the narrative is already set and little can be done to affect it, what’s the point? As I’ve observed over the last few years since the BLM Riots of 2020, the activists have their opinion of the police, and it has not and does not seem like it will ever change. They called for police abolition in 2020, and because that is no longer politically expedient, they’ve reverted to spreading conveniently edited clips of police interactions on social media.

What’s the Solution?

Anti-police activists have had the megaphone for far too long, and too many police departments have succumbed to their demands time and time again. The result has been less trust of the police, not more. This form of transparency is institutional suicide.

Rather, ignore the anti-police activists and focus on the 80 percent of the population that is largely neutral toward the police. The 10 percent on either end is pretty much set in their opinions. Yes, rabid anti-police and overzealous pro-police activists are not the ones needing more transparency. It’s the rest of the population we keep seeming to ignore.

It’s a bit extreme to compare anti-police activists to terrorists, though they’ve acted like domestic terrorists plenty of times before. Regardless, it’s fair to say we shouldn’t be negotiating with people who seek our destruction.

The solution isn’t exactly tidy, but I’d argue rather than throw out transparency altogether, shift the transparency conversation away from an activist led discussion to a conversation between the rational everyday citizen and their police department. Listen to those people. The activists will never be satisfied, so why try to please people who can’t be pleased?

Put out a press release when the activists throw a tantrum to make sure the everyday citizen has both sides of the story. But stop letting the activists lead police departments around by the nose. Say no when they demand things. Say yes when the everyday citizen has a question.

It’s not that hard to differentiate who is who. Trust me.

This is a good article. I'd love someone to explore how the general falling trust in institutions that coincided with society getting so online has impacted policing. Transparency and community policing reforms have been effective in curtailing the kind of policing you heard about in the 80s and 90s, but almost every institution has seen trust erode as everyone continues to melt their mind with the internet.